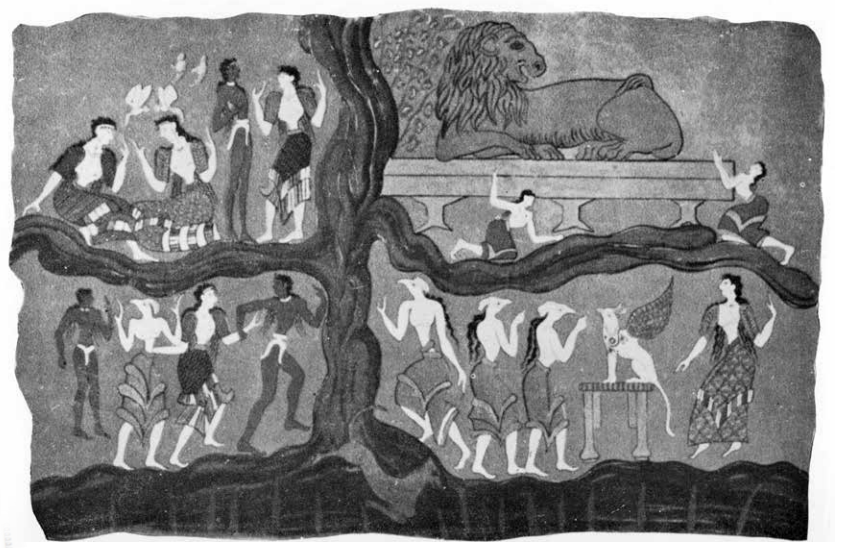

The animistic worldview-seeing consciousness, spirit, or life-force in all things-was once the global norm. From the shamans of Siberia to the Aboriginal Dreamtime, to Taoist alchemy and African cosmologies, the world was not a dead machine but a matrix of living forces. This core idea was not restricted to tribal beliefs or “primitive” spirituality, but also appeared encoded in major religious systems and sacred texts.

Animism Across Traditions

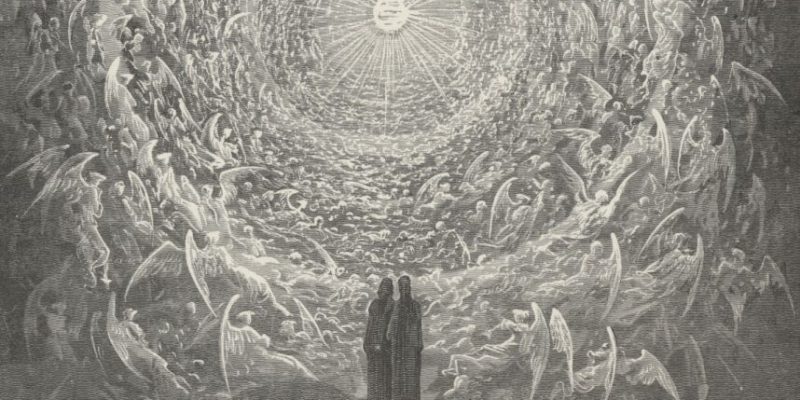

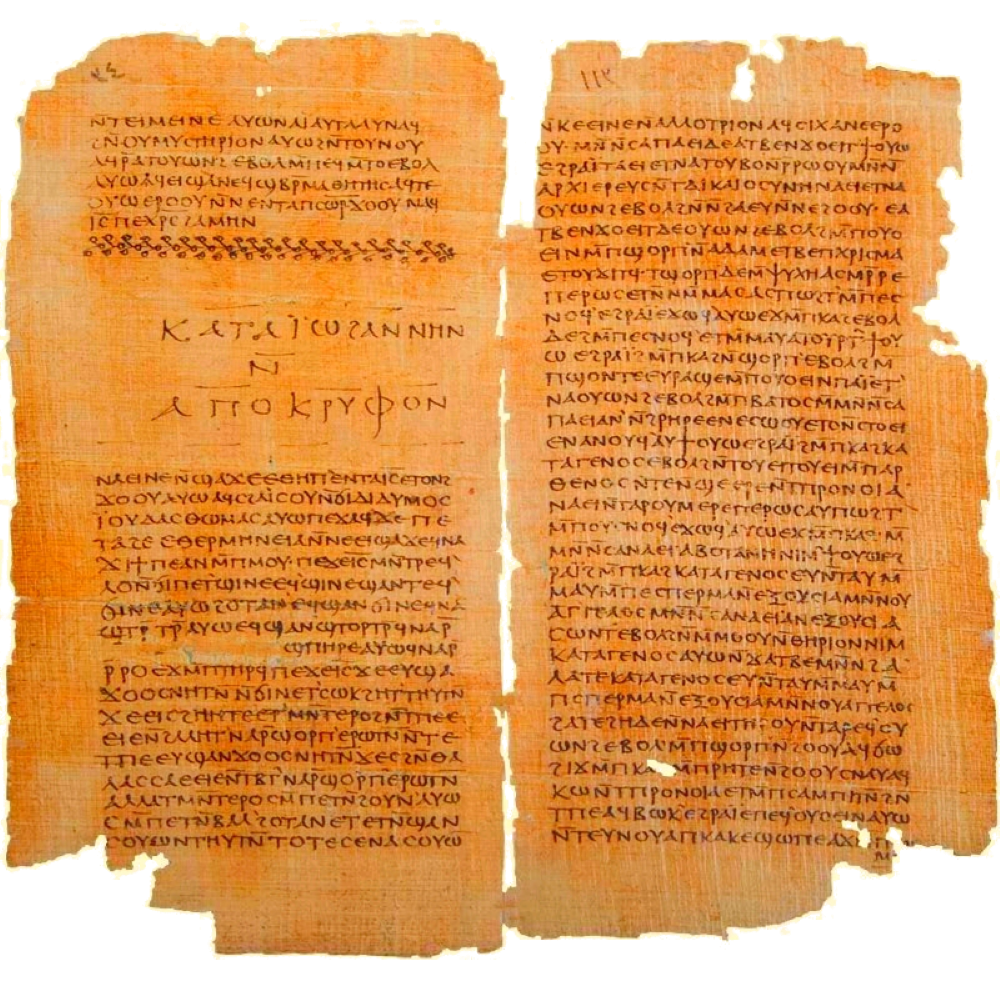

The animistic worldview—seeing consciousness, spirit, or life-force in all things—was once the global norm. From the shamans of Siberia to the Aboriginal Dreamtime, to Taoist alchemy and African cosmologies, the world was not a dead machine but a matrix of living forces. This core idea was not restricted to tribal beliefs or “primitive” spirituality, but also appeared encoded in major religious systems and sacred texts. In Gnostic traditions, such as those found in the Nag Hammadi scriptures, we discover a rich metaphysical tension between the transcendent source—often referred to as El Elyon or the Most High—and the lower creator god, Yaldabaoth, commonly associated with the Old Testament Yahweh. The Gnostics viewed the material world not as a neutral creation, but as something formed in ignorance or even hostility toward divine fullness (pleroma). Yet even in this fractured cosmos, the divine spark (nous) remains alive in all beings—an animistic remnant that can be liberated.