This paper explores the Gospel of Thomas as a radically interior, non-canonical text that challenges both the theological structure and institutional authority of mainstream Christianity. Through an analysis of key logia, particularly those emphasizing immanence, light, and self-knowledge, the paper situates Thomas within a broader context that includes Gnostic traditions, Eastern mysticism, and animist ontologies. The text’s aphoristic form and lack of narrative align it with meditative, non-dual traditions, suggesting that salvation is not a future event mediated by the Church, but a present reality accessible through direct realization. This study argues that Thomas represents not heresy, but an alternate Christian memory—one that offers potent resources for post-dogmatic spirituality in the modern world.

Jesus in the East

Recent scholarship and esoteric traditions alike have raised questions about the so-called “lost years” of Jesus—those unaccounted-for decades between his youth and the beginning of his public ministry. In the Gospel of Thomas, a non-canonical text discovered near Nag Hammadi in 1945, we find traces of teachings that diverge sharply in tone and form from the synoptic Gospels. The aphoristic, paradoxical sayings suggest a Jesus more akin to an Eastern sage than to the prophetic figure familiar from the New Testament. There has been much controversy surrounding these “so-called” missing years with some scholars claiming the young Jesus was busy at carpentering. Other researchers present evidence that Jesus spent much of this time in the East in Egypt, Greece, India, Tibet, and, Syria, and Persia.

The concept of the “Kingdom” as an internal state, the emphasis on self-knowledge, and the framing of spiritual enlightenment as a personal awakening align strongly with Eastern traditions—particularly Vedanta, Taoism, and certain Mahayana Buddhist schools. This parallelism has led some researchers to propose that Jesus may have encountered, directly or indirectly, the spiritual philosophies of the East, whether through trade routes, diaspora communities, or early travels. While speculative, such hypotheses offer a compelling alternative frame through which to interpret Thomas’s distinctive voice.

Animism in Thomas

The Gospel of Thomas challenges the dualistic metaphysics that came to dominate Western Christian theology. Its logia frequently suggest that spirit is not opposed to matter, but rather immanent within it. For example, in Logion 77, Jesus states: “Split a piece of wood, and I am there. Lift up the stone, and you will find me there.” This radical immanence recalls animist traditions, in which the divine is not distant and transcendent but present within all aspects of the natural world.

This orientation offers a bridge between Gnostic interiority and indigenous epistemologies. Thomas does not point to salvation through dogma or external ritual, but through direct encounter—through seeing, knowing, and integrating. The world is not fallen but veiled; the divine is not absent but unrecognized. In this way, Thomas anticipates contemporary eco-theological perspectives and resonates with a rising spiritual post-materialism that sees consciousness, rather than matter, as primary.

In light of these insights, the Gospel of Thomas can be read not only as an early Christian document but also as a profoundly integrative philosophical text—one that dissolves the boundary between matter and spirit, self and world, the sacred and the everyday. This aspect of the works, while not explicitly animistic text, does emphasizes inner, spiritual knowledge and the immanence of the divine within all things. This links Jesus and his more “personal” dialogue with ideas such as those of the mystical Minoans of the Bronze Age. In fact, this oneness thread is found throughout written and oral traditions throughout our history.

Logion 3 and the Kingdom Within

The central theme of Logion 3 of the Gospel of Thomas is that the kingdom of God I already within us, and that we do not need a clergyman to show us the Way! It is just a matter of bringing it out. The passage below attests to this.

“If those who lead you say to you, ‘See, the Kingdom is in the sky,’ then the birds of the sky will precede you. If they say to you, ‘It is in the sea,’ then the fish will precede you. Rather, the Kingdom is inside of you, and it is outside of you. When you come to know yourselves, then you will be known, and you will understand that you are children of the Living Father. But if you do not know yourselves, then you dwell in poverty, and you are that poverty.”

This passage reveals one of the most revolutionary metaphysical propositions in early Christian literature: that the Kingdom of God is neither remote nor reserved for the elect, but rather immanent—both internal and external, personal and cosmic. This non-localized Kingdom upends both the Jewish eschatological expectation of a coming messianic age and the emerging Church’s emphasis on mediated grace and ecclesiastical authority. It places the center of spiritual gravity within the self. This notion is timelessly true for the ancient Gnostics, claimed to be proverbs spoken by heavenly wisdom. The speaker is called “the living Jesus,” or the Jesus of eternity, and historical frameworks are Gospel of Thomas.

The insistence on self-knowledge as the gateway to divine awareness recalls the Delphic maxim gnōthi seauton (“know thyself”) and aligns closely with traditions in Hellenistic mystery schools, Indian Vedanta, and early Buddhist anatta inquiry. In each case, liberation or enlightenment is framed as a transformation of perception—not a shift in external circumstance.

The line “you will be known” also introduces a subtle Gnostic reciprocity between self-knowing and being truly known by the divine, suggesting that recognition of the divine within allows one to be recognized by the divine beyond. This reciprocal knowing defies the hierarchical theologies of both ancient Judaism and post-Nicene orthodoxy, replacing them with a relational and experiential model of salvation.

Furthermore, the contrast between knowing and “dwelling in poverty” reframes poverty not as an economic or moral state, but as a condition of alienation from one’s own divine origin. The use of the phrase “you are that poverty” is ontological—those who do not awaken to their own essence remain not just unaware, but metaphysically impoverished, fragmented from the source.

In this sense, Logion 3 may be read as a foundational text for both mystical Christianity and post-theistic spirituality. It does not dismiss the material world, but situates salvation in a shift of consciousness—a gnosis accessible not through doctrine, but through radical inner seeing.

The Metaphysics of Light in Thomas

Light in the Gospel of Thomas is not merely symbolic—it is ontological. It signifies the primal essence of being, the substratum of divine identity, and the medium through which gnosis becomes possible. Unlike the metaphorical light of canonical scriptures (e.g., “You are the light of the world”), the light in Thomas appears as something ontically preexistent, inwardly hidden, and spiritually recoverable.

Logion 24 states:

“There is light within a person of light, and it shines on the whole world. If it does not shine, it is dark.”

This formulation bears a striking resemblance to both Gnostic and Vedantic cosmologies, in which the soul (or ātman) contains a spark of the divine light, obscured by ignorance but never extinguished. The Gospel does not present light as something bestowed from above or mediated through sacrament, but as an intrinsic radiance waiting to be remembered and uncovered.

Logion 50 deepens this framework:

“If they ask you, ‘What is the sign of your father in you?’ say to them, ‘It is movement and repose.’”

This paradoxical sign of divinity—movement and repose—suggests a non-dual, dynamic stillness that mirrors the primordial rhythm of creation. Light here is not static illumination, but consciousness-in-motion, awareness that flows without friction. It is the ground of being and the animating principle of the awakened soul.

Thomas’s metaphysics of light challenges both Hellenistic dualism and orthodox Christianity’s externalized theology. It erodes the boundary between divine and human, offering instead a continuum of consciousness. The notion of a hidden light that illuminates when realized aligns closely with Eastern conceptions of bodhi, the awakened mind, and with mystical currents in Judaism (or ha-ganuz, the hidden light of creation) and Sufism (nur al-anwar, the light of lights).

Thus, the Gospel of Thomas presents not a doctrine but a vision: the human being as latent luminary, the cosmos as participatory, and salvation as the unveiling of a brilliance that was never absent—only unseen.

The Gospel of Thomas and the Crisis of Authority

The Gospel of Thomas stands as a radical challenge to the structures of religious authority—both ancient and modern. Unlike the canonical Gospels, Thomas contains no narrative of Jesus’s birth, death, or resurrection. It offers no institutional prescriptions, sacraments, or ecclesiology. Its Jesus speaks in riddles and revelations, but not in decrees. Authority in Thomas does not flow from priesthood, scripture, or apostolic succession, but from direct, unmediated gnosis.

This orientation runs counter to the centralizing impulse of the early Church, particularly as codified in the creeds of Nicaea and the hierarchical structures that followed. Where orthodoxy defined the boundaries of belief through councils, confessions, and canonical regulation, Thomas invites the seeker into interiority and paradox. Logion 1 states: “Whoever finds the interpretation of these sayings will not taste death.” In other words, salvation lies not in adherence but in awakening.

Such a vision posed a profound threat to emergent ecclesiastical authority. If the Kingdom is within, and if each individual can know the divine directly, then the need for institutional mediation—bishops, rites, theological gatekeepers—diminishes. The Gospel of Thomas reflects the very crisis that orthodoxy sought to resolve: the plurality of early Christianities, some of which resisted dogma in favor of mystical insight.

Moreover, the rejection of external leadership is thematized throughout the text. In Logion 3, Jesus critiques those who would point upward to heaven or downward to the sea. In Logion 39, he warns against religious officials: “The Pharisees and the scribes have taken the keys of knowledge and hidden them.” These sayings expose the mechanics of exclusion, the way institutional religion withholds transformative truth in the name of control.

In the context of modern spiritual inquiry, Thomas serves as a resonant counter-text—a recovery of Christianity’s esoteric stream. It echoes contemporary yearnings for authenticity, decentralization, and experiential spirituality. The crisis of authority it reveals is not merely ancient. It is perennial.

Thomas as Anti-Canonical Scripture

The Gospel of Thomas is not merely extracanonical; it is anticanonical in both spirit and structure. Where the canonical Gospels harmonize narrative and theology to support the emerging orthodoxy of the early Church, Thomas refuses narrative closure, doctrinal clarity, or theological hierarchy. It is aphoristic, recursive, and destabilizing—less a story about Jesus than a mirror held up to the reader’s own interior landscape.

This textual form itself constitutes a challenge to canon. Thomas offers no Passion narrative, no miracles, no Trinitarian scaffolding—indeed, nothing that lends itself to liturgical function or ecclesial authority. Instead, it positions the seeker as the locus of revelation. The text behaves like a koan: its sayings demand contemplation, not belief; interpretation, not obedience.

This alone would be enough to place it at odds with the canonical tradition. But Thomas goes further by undermining the theological presumptions on which that canon rests. Where the synoptics place salvation history in linear time—creation, fall, incarnation, atonement—Thomas presents spiritual awakening as timeless and perennial. Salvation is not a future event or a past sacrifice, but an ever-present possibility accessible through inner realization.

Moreover, the Gospel implicitly critiques the process of canonization itself. By preserving and transmitting Jesus’s sayings outside the sanctioned gospels, Thomas represents a parallel memory of Christ—a tradition that neither required nor submitted to ecclesiastical approval. Its very survival, hidden away in a jar in the Egyptian desert for over 1,600 years, speaks to the threat it posed and the counter-memory it preserved.

In a broader theological frame, Thomas stands alongside texts like the Gospel of Mary, Thunder: Perfect Mind, and The Dialogue of the Savior, as evidence of early Christianity’s radical diversity. It reminds us that what we call “heresy” is often simply the voice that history did not canonize.

As such, Thomas functions not only as a spiritual text but also as a critique of the mechanisms of religious power—an invitation to consider what has been excluded, and why.

Conclusion: A Living Gospel for a Post-Dogmatic Age

The Gospel of Thomas, though buried for centuries, has re-emerged at a time when its core themes resonate more than ever. In an age marked by spiritual pluralism, institutional disillusionment, and an accelerating search for direct experience, Thomas offers not a rigid theology but a set of luminous provocations. It invites the reader not to believe but to seek; not to conform but to awaken.

This Gospel challenges the boundaries between East and West, sacred and secular, ancient and modern. It reveals a Jesus who is not a distant savior but a mirror of the awakened self. In doing so, it restores a dimension of Christianity that was nearly lost—the esoteric, the experiential, the radically interior. The words of Jesus in Thomas seem somehow raw, but at the same time brilliantly enlightening. They are, in a very normative way, a truth we seem to have forgotten. In verse seems especially poignant for our modern world. Jesus said, “Whoever has come to understand the world has found (only) a corpse, and whoever has found a corpse is superior to the world.”

Thomas is not an answer but a doorway. It is scripture as process, truth as unfolding recognition. For those disenchanted with dogma yet yearning for depth, it is a gospel not only of ancient wisdom but of present possibility. It remains, perhaps more than ever, a living document—calling the reader not to worship the light, but to become it.

Author’s note: This paper was also published here.

Image Credits and Bibliography

Image Credits

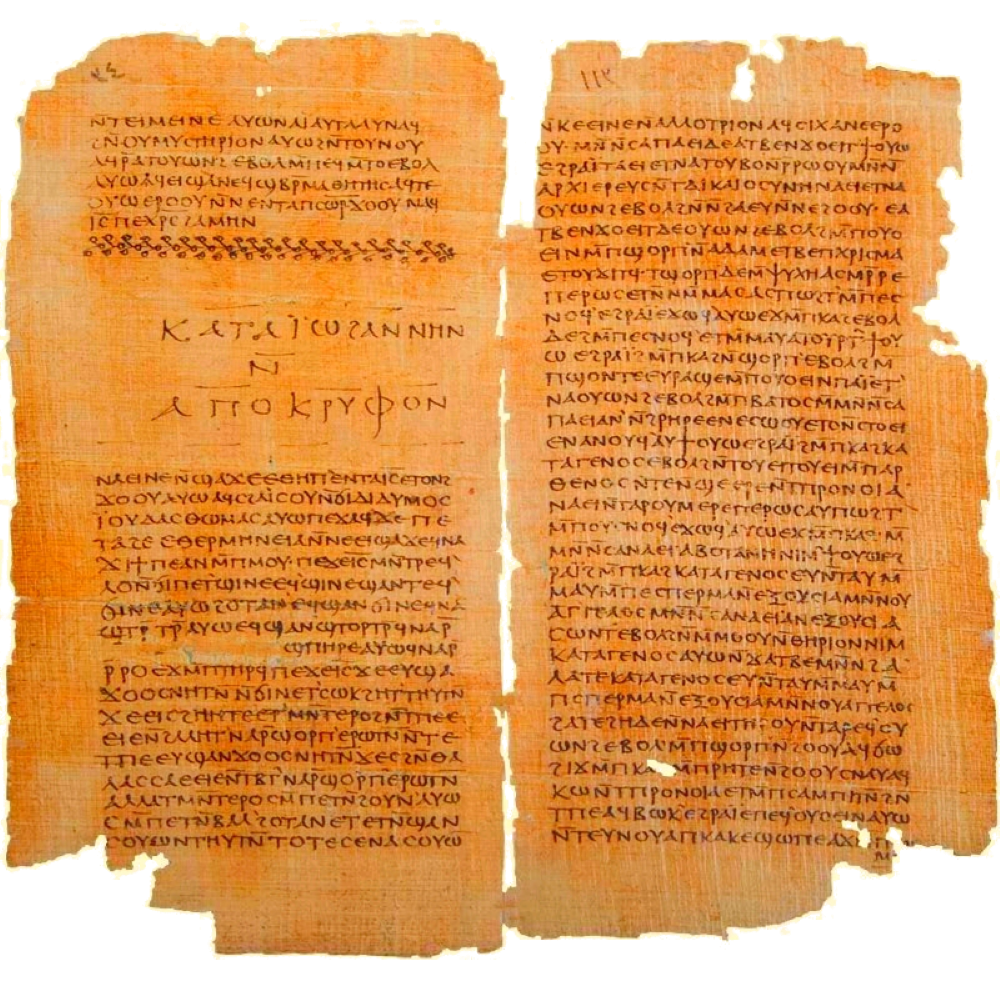

Fig. 1 – Gospel of Thomas Manuscript – Papyrus fragment, Nag Hammadi Codex II. Public Domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Fig. 2 – Paradise (Paradiso) illustration by French artist Gustave Doré.

Fig. 3 – Worn gold ring with epiphany scene: at right a worshipper invokes a tree, at left a goddess with two birds appears in the air. The standing central figure may be a god. Gsimonov CC0

Bibliography

DeConick, April D. *Recovering the Original Gospel of Thomas*. London: T&T Clark, 2005. King, Karen L. *What Is Gnosticism?* Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Leloup, Jean-Yves. *The Gospel of Thomas: The Gnostic Wisdom of Jesus*. Translated by Joseph Rowe. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2005.

Meyer, Marvin, ed. *The Gospel of Thomas: The Hidden Sayings of Jesus*. San Francisco: HarperOne, 1992.

Pagels, Elaine. *The Gnostic Gospels*. New York: Vintage Books, 1989.

Robinson, James M., ed. *The Nag Hammadi Library in English*. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

Dowling, Levi H. The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ, 1908

Miroshnikov, Ivan, The Gospel of Thomas and Plato, via University of Helsinki, 2020.

Turner, John D. “The Gospel of Thomas and the Platonic Tradition.” In *The Nag Hammadi Texts and the Bible*, edited by Charles Hedrick, 97–118. Leiden: Brill, 1986.

Luguern , Bernard, Commentary of logion 3 of the Gospel of Thomas: The location of the Kingdom of God, 2021

Benton, Layton, The Gospel according to Thomas (Yale University Press). 2021